How does distance complicate and intensify romantic feelings in ‘The Great Gatsby’?

- Aphra Jikiemi-Pearson

- Nov 21, 2025

- 5 min read

Written by Aphra Jikiemi-Pearson

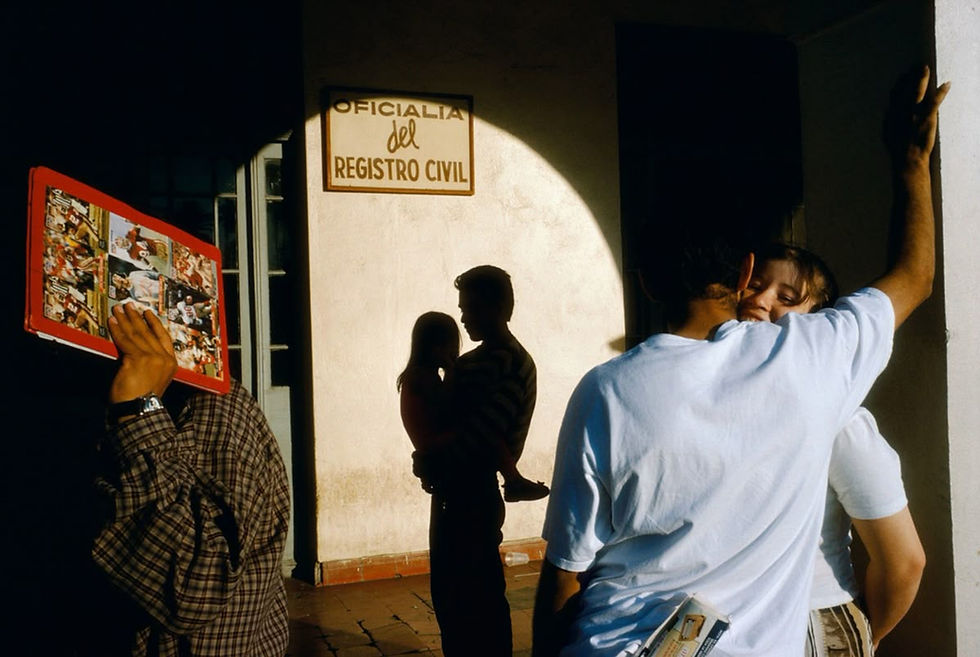

A green light, flashing dutifully at the end of a pier. Seen, maybe, but not recognised for what it is: a symbol of love, of dedication from afar. Get too close to the light, and all your ugly truths may be seen. The facade that the distance provides, the purple mist that covers the summit of a mountain, is burnt away. All your imperfect idiosyncrasies are revealed. You cannot hide anymore.

F. Scott Fitzgerald captured the complexities of romance and distance, and together how damaging and reverent they can be. Gatsby carried a beautiful, perfect version of Daisy in his heart, thinking only of and for her, always. The seemingly gaping abyss between the West and East Egg in his novel was impenetrable, uncrossable. It wasn’t. Nick Carraway made the journey multiple times. Gatsby was in love with someone who - as time passed - he didn’t know and in return, didn’t know him. He was embarrassed for that to change.

“You’re just embarrassed, that’s all,” and luckily I added: “Daisy’s embarrassed too.”

Gatsby relied on his reputation, his decadent and extreme parties to be the foundation for how he was perceived, most of all by Daisy. It happens in modern day too, you choose to post something, a select few images in a certain order, to control how other people think of you. Your friends - for Gatsby it was Nick - are mostly impervious to this. They know you, your bad jokes or whether your niche preferences, and they only play into the curated aesthetic you’ve made if it aids their own. Someone you have never met, never will meet, or haven’t seen in a while, will only know this perfected version that exists online or in their memory. Or at extravagant parties you host every weekend.

This then provides gaps in the imagination, to fill in characteristics and traits which align with how you view them, as a result of this controlled perception. Gatsby expected Daisy to willingly divorce Tom, and be married to him as if nothing had changed. Distance is a comfortable buffer, the chemical gap between neurones where messages are transferred; electricity. The neurones never meet. The science is complicated, as is love. Does falling in love with someone far away, maybe even unattainable, make it easier? After all, to not know someone is certainly simpler than knowing them. But what do you do when finally you are face to face? Seeing someone after a long time, or for the first time, is an exhilarating concept, because when creating this version of someone in your mind, you come to crave the truth. Our brains can't begin to fathom the complexity of being, the intricacies that make up a person. This curiosity can become a fixation, a hunger, a lust to know more. To know them deeply, irrevocably. To peel the onion of man layer by layer until you reach the nothingness at the centre, and only then you will know the truth. Reciprocated, however, it can feel embarrassing, humiliating, and shameful. You are bare in the face of their expectations. Raw and unfiltered, you can no longer control how they view you.

Arguably, Gatsby wouldn’t have died if he hadn’t met Nick, and had his desire to see Daisy answered. Had they remained shrouded from each other by mystery and the rosy sheen of nostalgia, could they have been happier? Apart, longing for what could’ve been, but alive at least.

The same might be said for Pyramus and Thisbe. Maybe the forbidden nature of their love made it all the more enticing. They might not have cared about each other if they were happily neighbours who occasionally had family dinners together. They wanted to learn about each other, fill in those gaps in their imagination, find the nothingness in the centre. Familial expectations and the wall between their bedrooms created distance, and although it wasn't major, it still hindered their ability to know each other entirely. Perhaps if they weren’t so curious about what they didn’t yet know of each other, they wouldn’t have ventured outside the city, and met their untimely ends. The tension of not knowing is the most powerful part, and although it can feel sickening at times, it can also be exciting and tantalising.

“Of course she might have loved him just for a minute, when they were first married—and loved me more even then, do you see?”

Distance also intensifies the jealousy of people who do know them, unfettered by an ocean or country borders. While Gatsby was sat in his mansion, longing for Daisy and a romance that no longer existed, Tom Buchanan was across the water; wealthy, a famous New Haven sportsman, and most importantly, Daisy’s husband. It seems, to Gatsby, to be unfair. He was there, his light flashing desperately for Daisy, while Tom was having an affair, but the ring was still firmly on his finger and on Daisy’s, and Gatsby’s finger was unchangeably empty. The realisation that other people know the details of this person you don’t, and could view them through the same lens that you do, brings with it a sinking feeling, and also a sense of betrayal. The betrayal is felt with a kind of petulance, what chain of events led to them being close, and us being so far apart? And why did they make it so apparent to me? Soon, you find yourself more consumed by this other person than your original focus. Gatsby had spent his life chasing wealth, and attention from Daisy. Tom had it and didn’t care for any of it. Comparison was inevitable. The realisation that you hold no claim over this person makes you want to claw back the miles between you and bring a sense of validity to the fragile, undefined thing between you both.

'his idea of the city itself, even though she was gone from it, was pervaded with a melancholy beauty.’

The distance can morph from something merely physical, easily breached by a plane ticket, to a more epistemic one. Aristotle felt that knowledge came from observation and experience. To understand someone fully, he believed, you require interaction and familiarity rather than just abstract knowledge. Gatsby and Daisy were separated by an epistemic distance. They didn’t know each other, just facts about their past selves that could no longer be applied. Aristotle couldn’t have predicted the use of text and instagram posts, or the meaning that our generation would place on seemingly useless notifications. Would he constitute a long snapchat streak as a degree of familiarity? It's easier to send a meaningless picture every day than engage in entertaining conversation with someone every day. Building rapport can happen with anyone if you know each other for long enough, or fall into a routine of seeing them often. In this case, distance can differentiate a relationship that occurred out of proximity from one that is more a stroke of luck. A discussion, even more so an entertaining one, between two people, who have no obligation to talk to each other, can hold more weight than people who do.

With this in mind, maybe Gatsby and Daisy were starcrossed, fated to be involved with each other somehow, for their whole lives. It was chance that Nick spent the summer there, was Daisy’s cousin and Gatsby’s neighbour. So it could be argued that their relationship was different, that they were bound to be repeatedly brought together by chance and pulled apart again by circumstance. Did the distance and time apart lend their romance a separate quality that made it feel more poignant, or were they both relying on nostalgia? It could’ve been a normal teenage fling that over time became an idealised narrative to them both. They both clung to the memories of their romance, trying to recreate it as if no time had passed, which alongside other factors, played a large role in their demise.

—

“Can't repeat the past? Why, of course you can!”

Comments